SCROLL DOWN TO READ THE POST

Teaching Genre Conventions From a Fan’s Perspective

Archetypes… or Clichés?

Here’s a question that I rarely see asked at SLJ or in any of the circles in which I travel: are genres ultimately limiting to both creators and readers? Why or why not?

If students aren’t already well aware of it, you may want to point out that genre fiction is sometimes denigrated relative to the ostensible artistic value of literary fiction. In fact, with this in mind, you might want to share Ursula K. Le Guin’s famous challenge to the science fiction community in the 1970’s: that genre fiction should aspire to being held to the same standards as literature rather than simply settling for fan approval (by the way, you can find this text in The Language of the Night). So do your students agree or disagree with this stance? Their opinions on the matter are worthy of an extended dialogue not only because it could clarify their thinking about Genre-with-a-capital-G, but also because any metacognition about their criteria for “quality text” should enhance their critical thinking skills generally.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

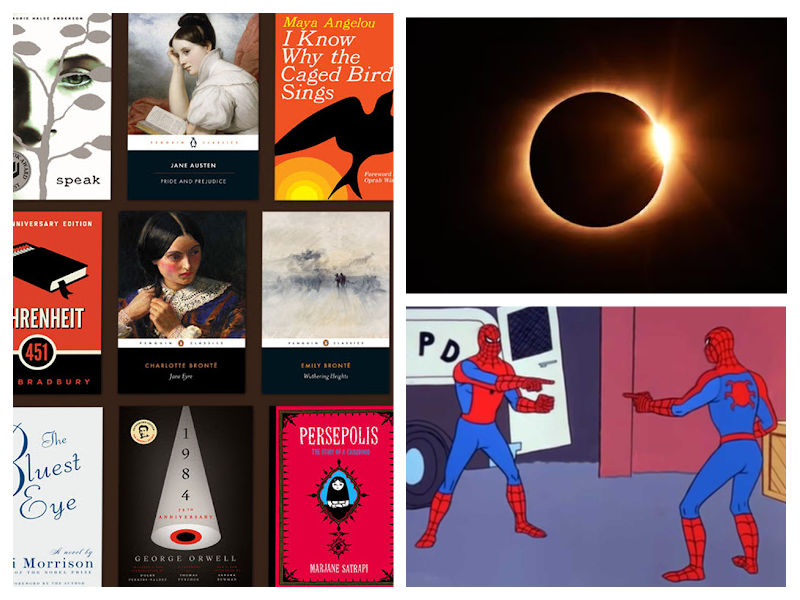

Point out that this very perception of lowered standards is one reason why genre fiction is looked down upon in some quarters. Another reason is the impression that individual genres endlessly recycle the same ideas and even the same narrative devices. Explain to students that creators walk a fine line in terms of valuing originality and satisfying fans’ expectations from the given genre—a trade-off that recalls Victor Watson’s same-and-yet-different dialectic regarding series fiction (in the seminal Reading Series Fiction). As a solution to this apparent conundrum, clarify the distinction between archetypes and clichés, explaining that one’s perspective toward a given genre makes all the difference.

Horses, six-shooters, rugged individualism, sweeping vistas punctuated by blazing sunsets, and a general air of borderline anarchy—it’s easy to identify the genre these ideas and images evoke. But while some may view these as the clichés of the Western, a fan might see them as enduring archetypes. After all, they provide powerful ways to concretize themes concerning individual courage and the fragile bonds of society, and to dramatize both “good vs. evil” and “man vs. nature” conflicts. In fact, archetypes are those story elements that help signify “genre” in the first place: if we too quickly dismiss them as clichés, a good portion of any given genre would probably evaporate. But can such crucial elements still be clichés? Of course they can, but the important thing to stress to students is the handling of such elements by a creator—if it’s a form of shorthand that does nothing but signify the genre, then the reader is likely in the midst of clichés. The issue of readers’ perspectives, expectations, and prior experiences is still vitally important, however. That’s because the fan-reader will demonstrate much greater patience with the text, waiting for what might initially seem like clichés to reveal themselves as skillfully wielded archetypes instead.

Horses, six-shooters, rugged individualism, sweeping vistas punctuated by blazing sunsets, and a general air of borderline anarchy—it’s easy to identify the genre these ideas and images evoke. But while some may view these as the clichés of the Western, a fan might see them as enduring archetypes. After all, they provide powerful ways to concretize themes concerning individual courage and the fragile bonds of society, and to dramatize both “good vs. evil” and “man vs. nature” conflicts. In fact, archetypes are those story elements that help signify “genre” in the first place: if we too quickly dismiss them as clichés, a good portion of any given genre would probably evaporate. But can such crucial elements still be clichés? Of course they can, but the important thing to stress to students is the handling of such elements by a creator—if it’s a form of shorthand that does nothing but signify the genre, then the reader is likely in the midst of clichés. The issue of readers’ perspectives, expectations, and prior experiences is still vitally important, however. That’s because the fan-reader will demonstrate much greater patience with the text, waiting for what might initially seem like clichés to reveal themselves as skillfully wielded archetypes instead.

With this sense of “genre as fans’ territory,” guide students to be critical of clichés they encounter as readers and to avoid using them themselves when they’re in the role of creator. To this end, consider making a wall chart or a shared electronic document that categorizes clichés by genre. You can present the list below as a springboard, and ask students to identify the genre or genres in which they appear, drawing upon their fannish background knowledge as needed. For fun, they could even provide examples of texts that contain these cliches. And finally, as an added challenge from the heart of the English curriculum, you could have them cite the story element that forms the basis for the cliché—is it theme, dialogue, setting, plot, or character?

“Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One Before…”

- A jewel, weapon, or ancient relic with supernatural or mystical power, thus making it desirable to one or more main characters.

- A kindly old mentor—often killed at some point to prompt the protagonist’s revenge motive.

- The whole world thought me mad… but I’ll show them!

- Suddenly, there are rats. And they appear in a way that’s always inconvenient (and sometimes frightening) to the good guys, often in places where there is no logical reason for them to be present (i.e., there’s no food or water).

- “Boy Meets Girl” structure: meeting cute; falling in love; the breakup of the romance; “boy” gets “girl” back again, usually through some act of redemption or clearing up a misunderstanding.

- Evil people are ugly or misshapen in some way.

- This town isn’t big enough for the two of us.

- A mobile phone that doesn’t work because either a) the battery is low or b) it just can’t get a signal.

- Fight scenes in empty warehouses or dark alleys.

- I didn’t come here to… make friends/start trouble.

- Time travelers who coincidentally find themselves in the middle of some grand historical event, not simply in an out-of-the-way place experiencing everyday life.

- Sad, sinister, tragic or haunting things that happen in inclement weather—usually a dreary rainstorm.

- You… complete me/ are my soulmate/ are my other half/ etc.

- A car chase results in a vehicle endangering sidewalk vendors or cafes, or plowing through a plate glass storefront.

- Fight fire with fire/ an eye for an eye / give them a taste of their own medicine / etc.

- Villains giving speeches to heroes at the climax of the story (parodied as “monologuing” in The Incredibles); heroes returning the favor by giving briefer speeches, sometimes just a one-liner, when they prove victorious a scene or two later.

Okay, you get the point. Students can certainly identify clichés even if they haven’t thought about them much, especially in regard to their own fandoms. The key thing to remember is that our own cliché-detectors are informed by an adult perspective with decades of reading and media consumption behind it; to students, though, the same items aren’t automatically hoary and lazy–they’re fun, even fresh if the students are young enough, and may even speak to deeper archetypes in what are becoming beloved genres.

Filed under: English, Fandom, Print Media, Transliteracy, YA Literature

About Peter Gutierrez

A former middle school teacher, Peter Gutierrez has spent the past 20 years developing curriculum as well as working in, and writing about, various branches of pop culture. You can sample way too many of his thoughts about media and media literacy via Twitter: @Peter_Gutierrez

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

Review of the Day: My Antarctica by G. Neri, ill. Corban Wilkin

Exclusive: Giant Magical Otters Invade New Hex Vet Graphic Novel | News

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

The Classroom Bookshelf is Moving

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT