SCROLL DOWN TO READ THE POST

Definitions

Me: Ugh, I have to define Young Adult Literature for this blog post.

My husband: Huh. Is that why you’re making To/From gift tags by hand?

Me: Maaaaaaybe?

What is young adult literature?

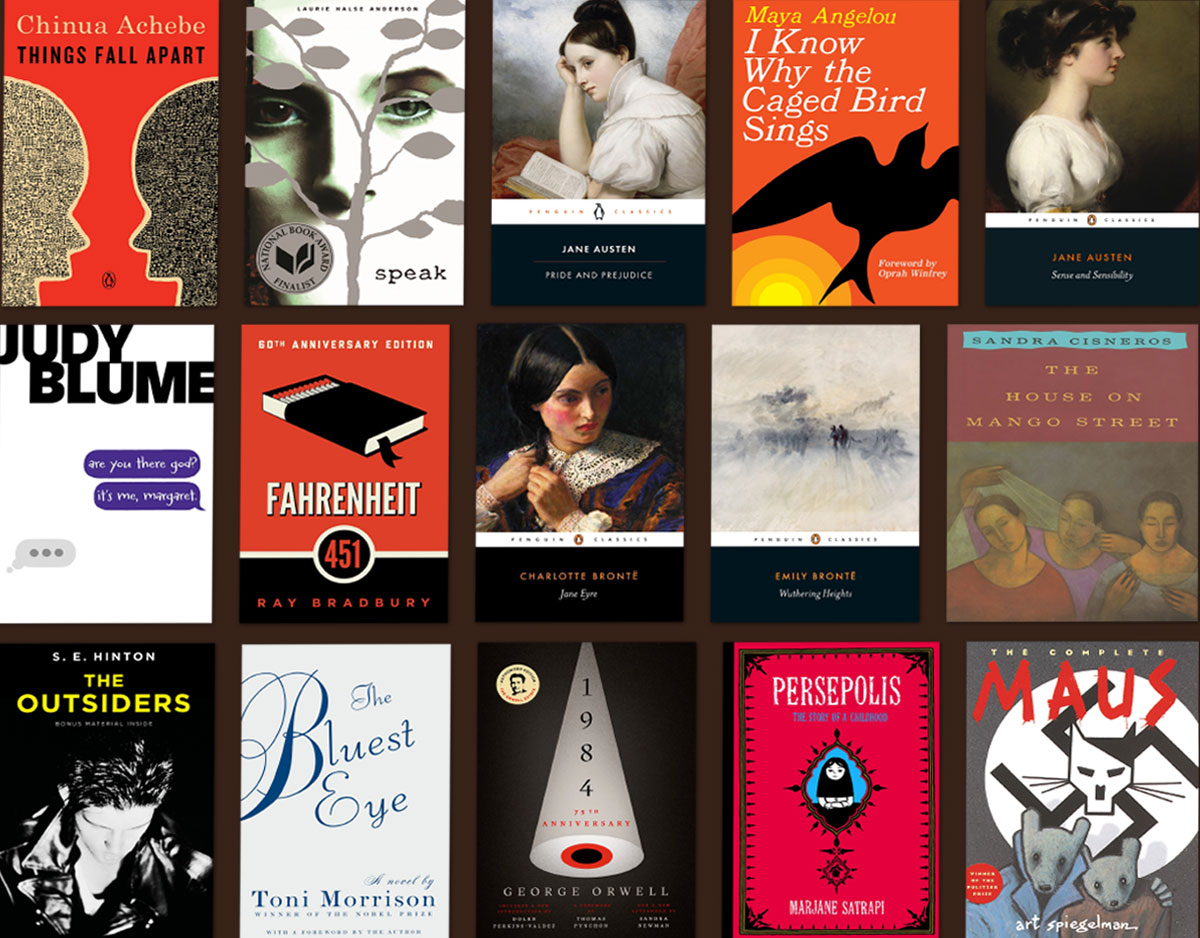

We’ve spent some time talking around this issue but not directly addressing it for the length of a blog post. The closest we’ve come to any kind of definition is in Karyn’s post (and the comments) on Paper Covers Rock. The same question was asked (indirectly) in my post on A Monster Calls when people wondered about the audience for that title. Oh, and we had another discussion on nonfiction for teens in the comments of Karyn’s post on the year-end lists from Kirkus and SLJ.

We’ve already combed through the Printz policies and procedures pretty thoroughly. While the criteria don’t give a cohesive definition, the eligibility portion does state:

To be eligible, a title must have been designated by its publisher as being either a young adult book or one published for the age range that YALSA defines as “young adult,” i.e., 12 through 18. Adult books are not eligible.

So there’s clearly a definition of YA Lit, even if we are letting the publishers apply it. And, more recently and more helpfully (though not necessarily useful for our purposes here, or for Actual Printz’s purposes at the table), there’s a great description in the Morris Award P&P: “The work cited will illuminate the teen experience and enrich the lives of its readers through its excellence” (the guidelines also go on to use my most hated phrase “proven or potential appeal,” but that’s just me, and that’s an entirely separate topic).

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Between her Paper Covers Rock review and some of the comments, Karyn gave a nice, succinct definition of YA fiction: a story that is about the the business of adolescence, i.e., about the adolescent journey: one in which the protagonist grows from someone acted upon to someone who acts.

Wikipedia (Ha! I really don’t want to get to the work of writing this, do I?) defines YA as “fiction written for, published for, or marketed to adolescents and young adults, roughly ages 14 to 21.” While I’m generally content to go with the old “whatever my teens are picking up and reading counts as YA,” that doesn’t work very well for award committees. (Although I practice a very descriptive version of librarianing, committee work, by its nature, is more prescriptive.)

So here we go. Let’s start with the basics. How are we defining YA? (Fascinating, isn’t it, that Wikipedia has one, much older, age range and YALSA has something else, eh?) Printz policies clearly give us the 12 to 18 range, so that’s what we’ll go with.

The Printz policies rule out adult fiction, but don’t say anything about children’s books. Publishers assign books an age range, which is where things get complicated. Lots of books get pegged as 12 and up, which is easy. And of course there are the clearly-for-kid ranges, like pre-school to grade 4. But things get tricky when you look at books published for ages 10 to 12, or 10 to 14. While it’s nice to be all prescriptive and definite, life just doesn’t work that way in practice, and the divides between kids, tweens, and teens is pretty muddled.

And then. What is YA literature? Well. YA books are about what it means to be an adolescent — to be someone who is between, who is moving. Who is changing. Who is trying on faces the way you or I might try on hats. Who is coming to a new understanding about who they are and what that means. The Rock said “know your role,” and that’s certainly one thing that fiction for youth is about — understanding who you are and how you fit in the world. But for a book to speak to the teen experience, it has to go beyond that — it’s about knowing your role (knowing where you came from) so that you can define your role for yourself in adulthood. A book for teens is about someone who is beginning to tell the world what their role is, not listening to the world for clues and cues about their role.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Which leads me to Dead End in Norvelt. Jack’s summer begins badly: with a grounding. Even worse, he’s told to help ancient Ms. Volker because her arthritis has gotten so bad she can no longer write the town’s obituaries. It’s an episodic plot that eventually culminates in a murder mystery. It’s funny, it’s sweet, it’s full of fart jokes, and it’s for kids. Older kids, sure, but still: kids. Jack spends the entire novel figuring out how he fits in with adults and in his town. It’s a novel where he’s starting to Know His Role. (It also drags in the middle and the mystery is solved off screen and Jack doesn’t really get the pleasure of solving it….dude, it’s for kids.)

Which leads me to Dead End in Norvelt. Jack’s summer begins badly: with a grounding. Even worse, he’s told to help ancient Ms. Volker because her arthritis has gotten so bad she can no longer write the town’s obituaries. It’s an episodic plot that eventually culminates in a murder mystery. It’s funny, it’s sweet, it’s full of fart jokes, and it’s for kids. Older kids, sure, but still: kids. Jack spends the entire novel figuring out how he fits in with adults and in his town. It’s a novel where he’s starting to Know His Role. (It also drags in the middle and the mystery is solved off screen and Jack doesn’t really get the pleasure of solving it….dude, it’s for kids.)

As for teen nonfiction, I am sad to say that I cannot think of a The Rock quote to get me started on crafting a definition. I believe I will dodge this bullet by pointing out that Drawing from Memory is memoir, which is a slightly different sort of nonfiction. It’s similar to fiction because it’s essentially a journey, too, just a journey that actually happened.

As for teen nonfiction, I am sad to say that I cannot think of a The Rock quote to get me started on crafting a definition. I believe I will dodge this bullet by pointing out that Drawing from Memory is memoir, which is a slightly different sort of nonfiction. It’s similar to fiction because it’s essentially a journey, too, just a journey that actually happened.

Drawing is an elegant illustrated memoir, detailing Allen Say’s development as an artist up to the age of 15. Living on his own in Tokyo, Say decides to ask the great cartoonist Noro Shinpei to become his sensei and mentor. That act, the decision to take control of his education, almost makes me put this in the teen section…but in the end this is another story about someone figuring out where and how he will fit in with the adults in his life (although I suppose I could be persuaded to change my mind, should you choose to argue the point in the comments). The memoir ends with Say preparing to go to the US to live with his father, who does not support Say’s dreams of becoming a cartoonist. If the story were more focused on the obstacles that Say had to overcome in order to do his art — if he had to openly defy his grandmother or his father — I’d be more comfortable calling this a title for teens. But what this story is actually about is remembering and paying tribute to Noro Shinpei, and the important role he played in Say’s life and in shaping him as an artist.

Karyn and I are working as a sort of Fake Printz Committee, and this is the definition we’ve worked out. So for our purposes on this blog, I’m saying these two, by our YA Lit definition, aren’t contendas. Every committee has to grapple with these questions, though, and every committee is different. It’s, of course, very possible that the Actual Printz Committee will find their way to a different definition of YA Lit and disagree with us.

But what do you guys say? How do you define Young Adult Literature? Where do you think Norvelt and Drawing fit? Comments are open!

Filed under: Fiction, Nonfiction

About Sarah Couri

Sarah Couri is a librarian at Grace Church School's High School Division, and has served on a number of YALSA committees, including Quick Picks, Great Graphic Novels, and (most pertinently!) the 2011 Printz Committee. Her opinions do not reflect the attitudes or opinions of SLJ, GCS, YALSA, or any other institutions with which she is affiliated. Find her on Twitter @scouri or e-mail her at scouri35 at gmail dot com.

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

Passover Postings! Chris Baron, Joshua S. Levy, and Naomi Milliner Discuss On All Other Nights

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Crafting the Audacity, One Work at a Time, a guest post by author Brittany N. Williams

The Classroom Bookshelf is Moving

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT