SCROLL DOWN TO READ THE POST

Titanic: Voices from the Disaster (Is Not a Disaster)

Occasional guest blogger Joy Piedmont is back! She (unlike, say, Karyn) likes to read nonfiction, and has OPINIONS about it. Thoughtful, considered opinions. Making her a perfect candidate to guest write as we try to catch up on our nonfiction 2012 piles. So, with no further ado…

Titanic: Voices from the Disaster, Deborah Hopkinson

Titanic: Voices from the Disaster, Deborah Hopkinson

Scholastic Press, April 2012

Reviewed from final copy

What is good nonfiction?

I know, I know; you came for a review and I’m hitting you with the big questions right up front. Apologies.

Right, so, good nonfiction.

Actually, it’s what any good book is: engaging, honest (factually and/or artistically), moving. Reading isn’t just the consumption of information, it’s an act that must change us, even in a small way. Good books should force us to question, to cry or to shout; we should be moved. Good nonfiction can put you under a spell and make the real unreal. (And isn’t this the inverse of good fiction, making the unreal real?) Good nonfiction, like fiction, is transformative.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

When we consider this in light of the Printz, there is no reason why nonfiction can’t be in the conversation, and 2012 has been a particularly good year for YA nonfiction.

2012 was also the 100th anniversary of the Titanic’s sinking. The ship of dreams was, and remains, ubiquitous. The story has been told so often – and it was pretty much inescapable this past spring – that you wouldn’t be alone in thinking that the subject has been covered from every possible angle. James Cameron certainly didn’t push the Titanic into obscurity. (True confession: I saw Titanic during its original theatrical release four times. And yes, I cried every, single time. Sobs.) What Deborah Hopkinson does really well in Titanic: Voices from the Disaster — and this is what all great nonfiction should do — is pull the reader into a story you didn’t think you needed, or wanted to know.

Let’s be clear: this is a nonfiction book that will please readers who subsist on a diet of mostly fiction, but there is plenty of information alongside the narrative to satisfy folks who love facts. The trick is in how Hopkinson tells the story.

As far as stories go, it’s a difficult tale to tell. Everyone knows the ending (spoiler alert: the ship sinks). This is no easy thing for a writer, but Hopkinson creates a moving and gripping narrative by weaving together various eyewitness accounts, each with a unique perspective. It’s not just the method here that’s brilliant; it’s the execution. Hopkinson skillfully shifts perspective from stewardess Violet Jessop to the Collyer family traveling second class, from second officer Charles Herbert Lightoller to seventeen-year-old first-class passenger Jack Thayer, and to several others. Hopkinson uses their words whenever possible, and through their voices we discover the stories of countless other passengers.

The result is an emotional book about the wonder of humanity: our hubris, our courage, our will.

When she’s not describing the many individual tragedies that occurred on the night the Titanic sank, Hopkinson gracefully uses fact to explain or elaborate at various points. To describe the Marconi wireless system and Titanic’s wireless operations, Hopkinson begins the section with the stewardess Violet Jessop, using her words: “I thought of the man in the crow’s nest … surely an unenviable job on such a night” (p. 57). This quote transitions to a brief description of the crow’s nest as a means to see what’s ahead, and the new Marconi system that the Titanic’s wireless operators, Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, would be using. All of this occurs within two pages and manages to maintain the thrust towards the ship’s sinking, the inevitable climax.

While some brief background on wireless messages blends nicely into the narrative, Hopkinson (wisely) chooses to leave some of the denser material for special fact boxes that are really mini-chapters within chapters. Hopkinson uses this technique when describing why the Californian, the ship that was actually closest to the Titanic, never came. This description and the speculation are fascinating, but only as asides, existing just outside of the book’s main interest: the people. The book is laid out so that these occasional departures are visually set apart and attractive.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

In general, good design and consistency aid the reading experience. The text is set in ITC Avant Garde Gothic, a sans-serif font, which gives the text a modern, fresh look; dark gray boxes are used for photos and fact boxes, and thin dotted lines, in black or white, are used for borders. Very often photos are spread on whole pages to the edges, contributing to the immersive quality of the text. When Hopkinson writes about the beautiful grand staircase, her words help you imagine what it would have been like to be there, but the photo on the opposite page lets you see it with your own eyes. Photos, illustrations from the period, and primary documents embroider the narrative and lend weight to the text; yes, this happened, it may feel like fiction, but this is fact.

However, most of the facts and figures, including a glossary, and the official damage report and fatality statistics are appendices at the end of the book. Hopkinson has also provided rich material on her sources (including well-documented source notes for each chapter) and offers questions for budding researchers. The best of these supplemental sections is the material on the people in the book, containing great tidbits of information that didn’t fit in the main content. It is a poignant reminder that the “characters” were actual people with lives existing before and beyond the Titanic – although the tragedy never really left many of them. This supplemental section also reinforced my belief that Hopkinson did something extraordinary in this book, pulling together various lives, shaping their eyewitness accounts into a cohesive, engaging plot.

Impressive, absolutely. Perfect? Not quite.

Hopkinson’s use of concise and clear language is often one of the book’s strengths, but she tends to accentuate the end of chapters and sections with a single sentence paragraph: “The titanic needed help,” (p.85) for example, or “One by one, the lifeboats began to make their way to the Carpathia,” (p. 171). This kind of pacing can be effective when used sparingly to foreshadow or underline important events, but when every reader knows the ending, these pithy one-liners become the literary equivalent of a bombastic musical cue for a villain.

Unfortunately, this stylistic tic means the book isn’t quite on the same level as other Printz contenders this year, although it certainly earned its place on the nonfiction shortlist: it is a standout YA nonfiction title.

Filed under: Contenders, Guest Posts, Nonfiction

About Someday

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

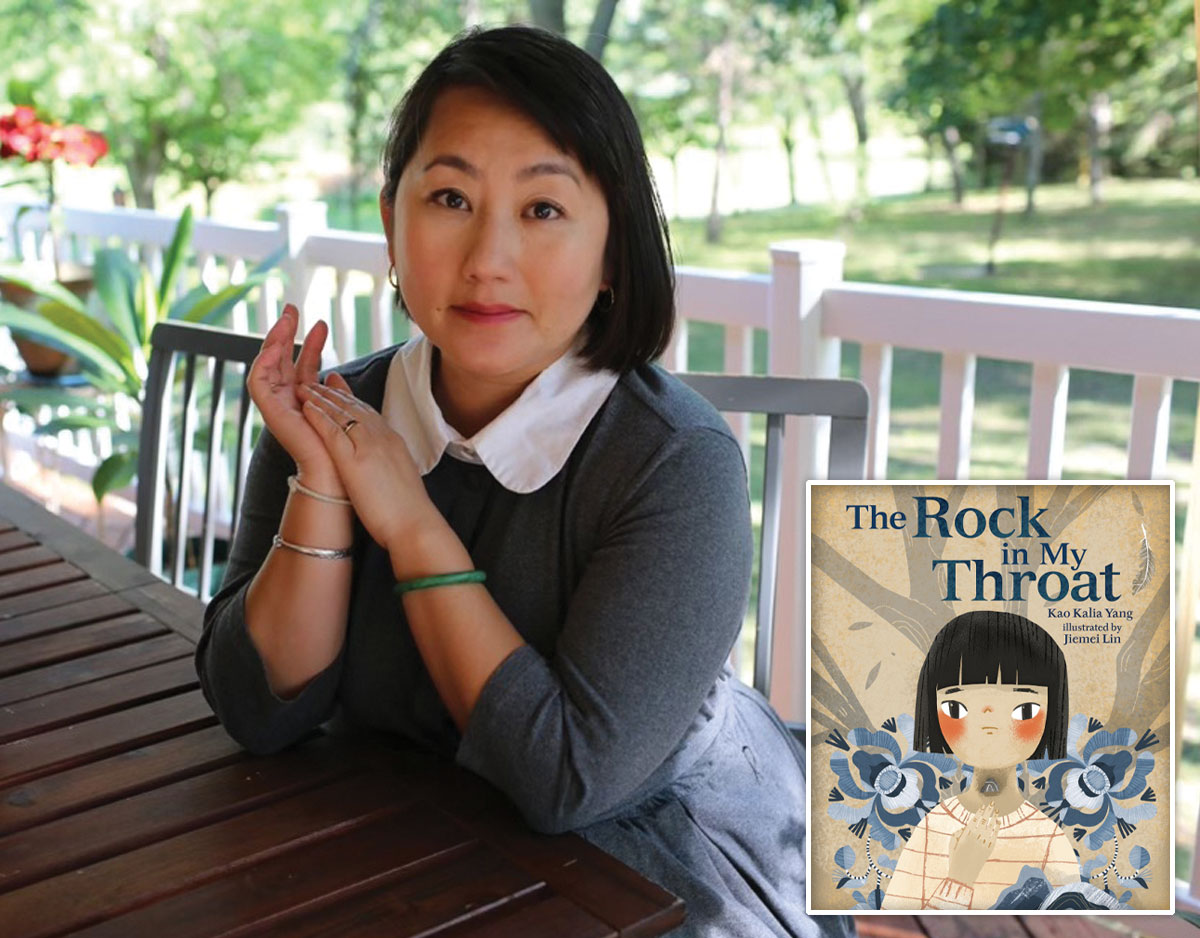

Passover Postings! Chris Baron, Joshua S. Levy, and Naomi Milliner Discuss On All Other Nights

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Crafting the Audacity, One Work at a Time, a guest post by author Brittany N. Williams

The Classroom Bookshelf is Moving

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT