SCROLL DOWN TO READ THE POST

There’s Dark Things In Them There Books!

Guys, you have to read this! The Wall Street Journal has made a stunning discovery — in Darkness Too Visible, we discover books with bad, bad things like “vampires and suicide and self-mutilation,” all done by the evil publishers and librarians and booksellers and others to deliberately “bulldoze coarseness or misery into their children’s lives.”

Clearly, the way to protect the innocence of children and teens is to prevent them from learning about the darker things in life. If you don’t know about it, it won’t happen to you! (Sadly, that is my half held belief about doctors which is why I rarely go to them. You’re not truly sick until the doctor says so.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Is this true? Take a look at Hush by Eishes Chayil, which shows just what happens when a community embraces such a doctrine. Obviously, I’m of the belief that ignorance and innocence are not identical; and that keeping teens from the books that will help them with difficult things under the belief that this makes the difficult things never happen does more damage than good. I’m also of the belief that once it’s decided that certain things should not be spoken aloud — incest, abuse, suicide — and not included in books, it makes it that much harder for those teens who do experience those things in life, either directly or indirectly, and people end up thinking that those people who experience those things should likewise be hidden. Not talked about except in a whisper.

I’m also of a belief in having the reader — any reader — choose their own books. If tomorrow all the dark YA books disappeared, the need those books fill would not go away, and those readers would either a, decide books don’t have anything for them and stop reading, or b, look elsewhere for those topics — such as the adult fiction shelves — and so would still be reading “those” books. (Discuss amongst yourselves the difference between a teen reading a YA book about suicide and an adult one. I think part of a teen’s rich reading diet should include books outside of YA, but, based on my own teen reading, sometimes reading an adult book for a subject you’re interested in is like buying a “one sized fits all” T-shirt. It gets the job done, but it doesn’t quite fit.)

The sad thing about Darkness Too Visible is that there is just so much there that is off kilter that one could almost write a book in response. Let’s start with the “this is all new!” As an aside, one expectation I have of people writing about books is that they have depth of knowledge. I don’t care where or how they obtained the knowledge — they may be 18 or 48 or 81, with or without a PhD in literature, be a scholar or just a passionate reader. Which means that statements like “Pathologies that went undescribed in print 40 years ago, that were still only sparingly outlined a generation ago, are now spelled out in stomach-clenching detail” and “As it happens, 40 years ago, no one had to contend with young-adult literature because there was no such thing” really bother me. Especially when the author points out that the book that changed it all was written in 1967. Which — wait for it — 44 years ago. So, technically, even assuming arguendo that the author is correct, should have been “45 years ago.” Six Boxes of Books lists just some of the authors who were writing books for teens before 1967.

Some scattered thoughts: the article begins with an anecdote about a mother not being able to find any books for teens in a bookstore other than vampires, suicide, and self-mutilation. Other than the obvious –really? No Ally Carter or Meg Cabot? No Anthony Horowitz or Kirby Larson?– the moral of that paragraph: booksellers and librarians do matter, because they would have been able to point out such authors to the mother. As budgets are cut, as bookstores and libraries disappear, the connecting of the book a reader wants with the reader is just going to get that much more difficult. The mother and her child want books without vampires, suicide, self mutilation? Terrific! They exist. But they may as well not exist if we don’t have effective ways of connecting the reader and the book. As further evidence of the problem, the mother in question says in the comments, “I want to add that a B&N employee noticed me leafing through 78 books, and offered to help. (Because she had not in fact read any of the books for sale, she kind of kept me company more than helped, but it was still something.) She told me I was far from the first to complain.” What we have here is B&N’s failure to train employees, hire qualified employees, have subject area specialists, and, possibly, have a diverse selection (if, in fact, Ally Carter was no where to be seen).

The characterization that this is all new — that books like this have never existed! At least not at bad as this! Makes me want to reread Steffie Can’t Come Out To Play (1978) (which taught me if you run away to New York City, don’t talk to the nice stranger at Port Authority because in 24 hours, he’s your pimp and you’re walking the streets for money) and To Take A Dare (1982) (lesson: always take all your pills for a STD or it will end badly, and it’s OK to hitchhike as long as you carry a big knife and aren’t afraid to use it).

And then there is this: “ But the calculus that many parents make is less crude than that: It has to do with a child’s happiness, moral development and tenderness of heart. Entertainment does not merely gratify taste, after all, but creates it,” and “If you think it matters what is inside a young person’s mind, surely it is of consequence what he reads. This is an old dialectic—purity vs. despoliation, virtue vs. smut—but for families with teenagers, it is also everlastingly new,” and “No family is obliged to acquiesce when publishers use the vehicle of fundamental free-expression principles to try to bulldoze coarseness or misery into their children’s lives.”

There’s this: “Foul language is widely regarded among librarians, reviewers and booksellers as perfectly OK, provided that it emerges organically from the characters and the setting rather than being tacked on for sensation.” So… the author is saying that books shouldn’t contain those bad, bad words. Yet, guess what? The WSJ, in a sexist sidebar (some books are for boys only, some for girls only), recommends a book that includes the “c” word. Maybe it’s OK for young men to read that word, but not the “f” word?

And, finally, this: “In the book trade, this is known as “banning.” In the parenting trade, however, we call this “judgment” or “taste.” It is a dereliction of duty not to make distinctions in every other aspect of a young person’s life between more and less desirable options. Yet let a gatekeeper object to a book and the industry pulls up its petticoats and shrieks “censorship!” Here’s the thing. Make that distinction for your children and teens? Fine. The Duggars can decide what Jinger, Josie, and the Js read or don’t read. But they cannot decide it for other parents and guardians. And with the fearmongering in this article, the author is saying it’s a “dereliction of duty” rather than a parental judgment call about what their child reads or doesn’t read. That’s fighting words. And, yes, it does cross the line from “what is right for my child” to “what is right for all children.” This article is full of “no parent in their right mind would want a child to read such garbage.”

What this article ignores is the questions of why people read what they do — one of the areas I find fascinating just because, and also because it helps with readers advisory. Some kids in terrible circumstances read about kids in terrible circumstances and find comfort and hope, even in the bleakest book; others live it, so don’t want to read it. Some read for windows; some, for mirrors. Some kids in crappy circumstances want to read about kids who have it worse off, so they can think, “at least my life isn’t bad as so and sos.” Some teens love literary books; some teens get so much literature during the school year that recreational reading is all about the popcorn. Each reader’s “popcorn” is different; for some it’s vampires and horror, for others it’s books that make them cry, like books about suicide, for others its books that talk frankly about what is whispered around school, like self-mutilation. Often, the full diet of what a person reads, teen or adult, cannot be judged by one or ten books, or one month, or a summer. Readers get obsessions — my Sylvia Plath obsession lasted years.

Trying to identify what a reader wants from a book, so recommending the right fit, is one of the hardest things about readers advisory and one of the things that is least respected. It’s not as simple as similar plot points or the same author. It can be both about giving a child what they want and what they need. To use an anecdote from my own childhood: I was reading the Oz books like crazy cakes in about third or fourth grade. So my mother “upped the game” by seeing what I wanted (adventure fantasy about made up lands) and upped the literary level of what I was reading by handing me The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe which I never, ever, would have picked up on my own because, really? Wardrobe? Boring. The result was a lifelong love for C.S. Lewis.

As for the other bleak books — if a kid doesn’t want to read it, don’t make them. But if a kid does want to read those books, is reading those books, and the adults in their lives are concerned, talk to your child. There are so many reasons for that teen reading that book (interest, a friend with a problem, their own problem, rebellion (you don’t want me to read it so I will), fascination with something that doesn’t exist at all in their world, wanting sad books, etc) and each of those is so different and each starts a different type of conversation, including “well, if that is what you want to read, you may like (insert title of other book.)”

What other folks have to say, in no particular order other than when I read them. Link to your own posts in the comments; I will do my best to edit this and add those posts during the coming week.

The Twitterverse became enraged and responded, using the #yasaves hashtag. Have a few hours? Search for those tweets.

Stephanie Lawton, YA Under Attack: Heaven Forbid We Address Reality. Some gems: “because it was not discussed 40 years ago, we should not discuss it now. This is sound reasoning if ever I heard it. Examples: showing pregnant women on TV; couples sleeping in the same bed; anything related to “menstruation.” OH GOD! MAKE IT STOP!”, “As a relatively conservative parent of young children, I take offense to this. There is a difference between being the gatekeeper for your own children and telling everyone else’s what they can and can’t read,” and “A better approach, in my opinion, is to let these books open a dialogue among children and parents. Discuss the issues. Read the book along with your teen.”

Steph Su Reads, The Only Thing I Really Hate. “Again, there’s not much being said that hasn’t been said before, so I want to focus on what I believe is the real “enemy” here: the attack on change and progress, and the lack of openmindedness.”

Online, WSJshares @LibbaBray’s response. Far as I can tell, there is no link to Bray’s response at the original article and no indication that WSJ’s print readers will get that rebuttal.

Zoe Marriott, Responding to the Wall Street Journal Article. “The world has never been bright, cheery and happy and uncomplicated. Kids have always been abused. They have always suffered in silence, hurt themselves and others. Children have always, always, always partaken of the pain and agony of humanity. They have always had to live with the same darkness, the same wars, the same nightmares as adults do.”

Bookalicious Pam, TMI – YA Saves. “People ask me all the time why I read and love YA. Why I spend my time championing children’s literature. I usually say “I like the low page count and the stories are interesting”, or some other noncommittal dribble. I never say what I should that “I wish so much these books would have been there for me.”

Edited to add:One of the really outrageous things in the article was the treatment of Cheryl Rainfield’s book, Scars. Here is Cheryl’s response. “There’s so much societal judgment about using self-harm, being queer, and often about being an incest survivor. People tell us not to talk about it, or blame us for what we’ve been through or what we feel. And that makes the pain so much stronger. I wrote SCARS to let other teens with those experiences know that they’re not alone, and that they can find healing, and to encourage people who didn’t have those experiences to have more compassion for those who did.”

Edited to add: Dr. Teri Lesesne (aka Professor Nana, The Goddess of YA literature) responds with How To Save A Life. “Those stories are wonderful and remind us how YA can save lives. But I want to talk about the other ways books can save. . . . IT ALLOWS READERS A SAFE HAVEN IN WHICH TO TEST THEMSELVES. … IT GIVES KIDS A CHANCE TO SEE THEY ARE NOT ALONE… IT DEVELOPS READERS. …IT DEMONSTRATES THAT, JUST BECAUSE THE BOOK IS WRITTEN FOR TEENS, THAT IT CAN INDEED BE A LITERARY EXPERIENCE.”

Edited to add: Salon, Has Young Adult Fiction Become Too Dark? “And no, not all of it is great literature. Remind me again when there was a time when there was nothing but great literature from which to choose? Critics like Gurdon are forever holding the dregs of the present up against the best of the past, which is an unfair and highly loaded argument. You can’t compare what’s crowding the shelves now with a tiny handful of classics that have endured.” “in the name of protecting teens, we can’t shut them off from the outlet of experiencing difficult events and feelings in the relative safety and profound comfort of literature. Darkness isn’t the enemy. But ignorance always is.”

NPR, Seeing Teenagers As We Wish They Were: The Debate Over YA Fiction: “Look: Once you’re talking about older teenagers, they read whatever they want from the world of YA and adult books anyway, if they happen to be readers, and if they aren’t readers, they aren’t reading the tough books about abuse and the apocalypse to begin with. They have already decided they don’t care about reading for pleasure. They have moved on. And with younger kids, like 13-year-olds? If they’re interested in dark themes, they’re going to find them, whether it’s in YA novels or something else. Curiosity about death or illness or suffering doesn’t have to be grafted onto 13-year-olds by fiction writers. ”

Blue Rose Girls, Darkness in YA Literature “I loved books that made me cry, and I loved books that made me think. I also liked books that made me laugh, that simply entertained me. I loved the classics. I also loved the fluff. Personally, I think that pretty much “anything goes” in YA lit, because before YA lit existed, teens were reading adult books. They still are. There is a need and a market for all kinds of books.”

Read Roger, Again? “Give me an author who is truthful and talented; spare me an author who writes to save lives. . . . If you’re a teen who is running your reading choices by your parents, grow up. If you’re a parent who feels compelled to approve your child’s reading, shut up. The books and the kids are all right.”

LA Review of Books, Better to Light a Candle than to Curse the Darkness “You know what, taste is a funny thing. What might be to your taste might not be to mine. But you can’t CHOOSE what my taste is. (I like caviar. I hate pineapple on pizza.) And teenagers have their own tastes.”

Barry Lyga, On the WSJ, YA and Art “I refuse to justify my art. Yes, my books are my occupation. My career. I don’t do them for free; I get paid. But I don’t write them because I get paid. The money’s a nice benefit. And I don’t write them to help kids or change them. That, too, is a nice benefit, one that I adore, one that humbles me every single time I think of it or see evidence of it. But I write because I am compelled to do so. Because to do otherwise would be to hack off my limbs and put out my eyes. Because the stories I tell chomp and chew and gnaw at my soul until I let them out. As long as there has been art, there have been naysayers and lack-a-wits jeering from the sidelines, mocking the efforts of those who create. I’ve dealt with these nincompoops my entire life and I’m just too old to give a damn what they think or say anymore.”

Laurie Halse Anderson, Stuck Between Rage and Compassion “I find myself shaking with anger. Why? First and foremost because this is opinion (badly) dressed-up as journalism. I expect better from the Wall Street Journal. Second, because I know how ridiculous and harmful the statements are.”

Indiscriminate Writes, Call for blogs/articles supporting Meghan Gurdon’s “Darkness Too Visible” article “I would like to add some links to blogs and articles that support Meghan Cox Gurdon’s Wall Street Journal article.”

Mud, Mambas, Mushrooms and Machines, Brightness Too Visible. “I was recently at the bookstore looking for board books for my son, and left feeling thwarted and disheartened. It was all barnyard animals making noises and counting and going to bed on time. It was light, light stuff. I left empty handed. How light are board books? Lighter than you think, sweetie. Insufferable lightness that would have been considered too sentimental or educational forty years ago* is now the norm: fluffy bunnies who don’t get into mischief, well-behaved children who love learning manners.” “* I assume. I haven’t researched this” parody

Teaching With Zest, Navigating the Darkness: In Defense of Young Adult Literature “Life is not a fairy tale, and adolescents seldom want to pretend that it is. Life for them can be tumultuous, and literature that acknowledges that tumult does not, as Gurdon suggests, normalize it Instead it normalizes the fear, anger, and uncertainty that accompany tumult. YA lit gives readers a way to step outside of themselves to think about tumultuous experiences. These books offer a safe means of exploring the darkness, and through this exploration, adolescent readers can find a light to illuminate the joy and beauty that lie beyond the darkness.”

Sonderbooks, YA Saves “Librarians are knocked in the article for giving dark books to teens. We’re actually quite good at finding the right book for the right reader. And we could even find a book that would make that mother happy. And if she let her own teen pick a book, we could find a book that would make her happy.”

The Insane Scribblings of a Madwoman, YA Books: Too Dark or Hitting Too Close To Home? “Trust your kids. Talk to them. Read with them. Read before them if you feel you have to. Don’t criticize an entire genre just because they’re exposing reality for what it is through artistry and fiction. And mom, thank you for trusting me with my reading.”

I Read to Relax, The WSJ, “Age Appropriate”, Censorship and #YASaves “YA is an age group…not a genre. Which means…huh…there are about a hundred different types of YA books. That means that there IS a book out there for every teen reader. I swear!”

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Elizabeth Burns

Looking for a place to talk about young adult books? Pull up a chair, have a cup of tea, and let's chat. I am a New Jersey librarian. My opinions do not reflect those of my employer, SLJ, YALSA, or anyone else. On Twitter I'm @LizB; my email is lizzy.burns@gmail.com.

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

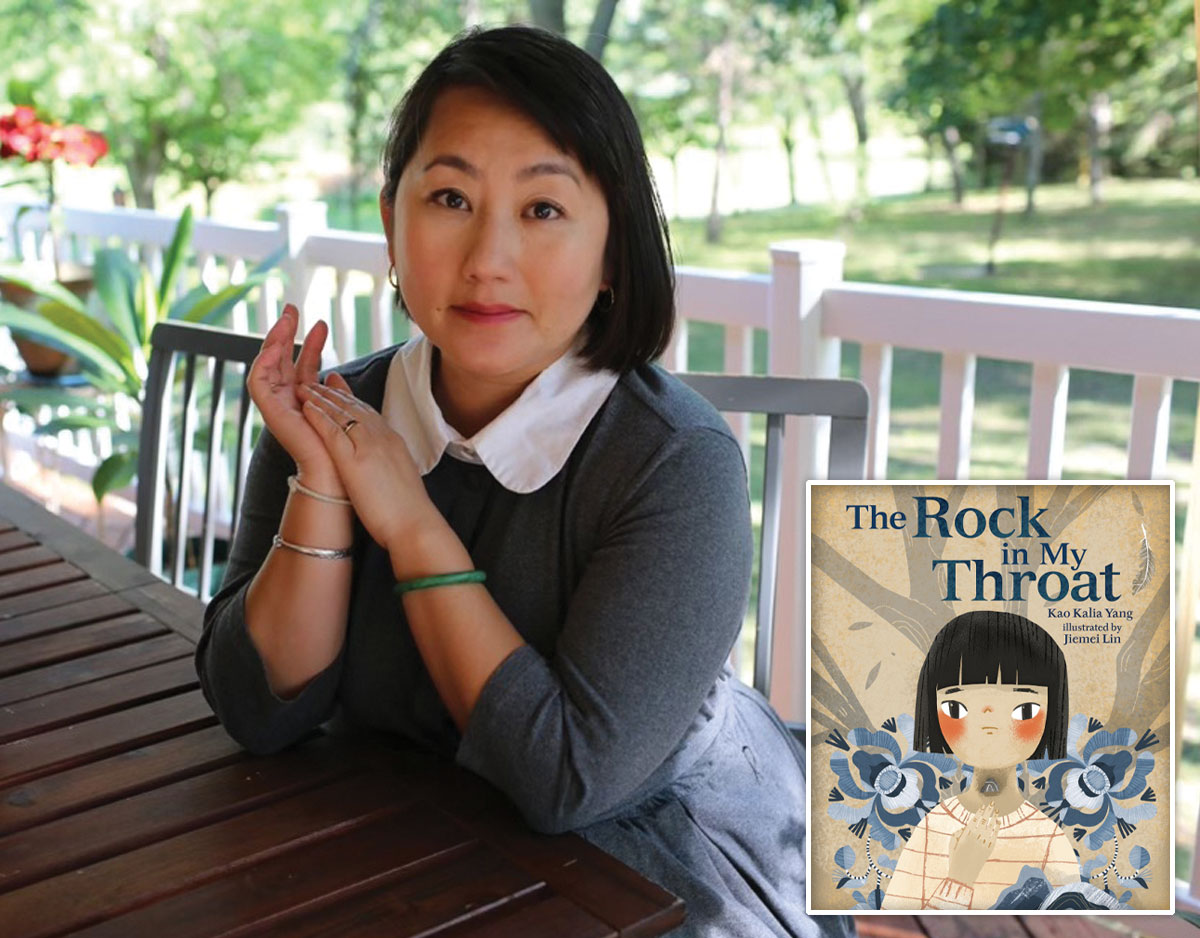

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

In Memorium: The Great Étienne Delessert Passes Away

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Finding My Own Team Canteen, a cover reveal and guest post by Amalie Jahn

The Classroom Bookshelf is Moving

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT