SCROLL DOWN TO READ THE POST

Death by Media: The Hunger Games and Teen Authenticity (Part 1)

Reasons to Resonate

Ever wonder what Katniss might make of all the hoopla currently surrounding The Hunger Games?

It’s a question that might be good to ask both of ourselves and, more pointedly, of the millions of young fans of the Suzanne Collins trilogy.

Even if we just confine ourselves to the first of those novels—whose extravagantly-anticipated screen adaptation bows this week (as if you didn’t know)—it’s clear that one of the author’s major themes is a deep suspicion of mass media… and specifically “media events” of the sort that The Hunger Games has itself now become.

Certainly there are more obvious reasons for why readers have responded so strongly to this über-bestseller: an honesty of voice that typically marks the best of YA fiction, a terrific immediacy in terms of storytelling, and a gripping sci-fi/adventure yarn at its core.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

On a thematic level, there’s also plenty to appeal to teens and tweens, including the mythic notion that somehow they’re being sacrificed in the present for failures or compromises in the past. Looking at the novel’s success through the lens of history, it’s worth noting that its young readers were the first to begin schooling during the era of high-stakes testing ushered in NCLB—they knew all too well about the pressures to succeed and bring (AYP) honor to their (school) “Districts.” More dramatically, The Hunger Games was published as the financial crisis of 2008 neared the meltdown stage, just four days, in fact, before the U.S. Fed Chairman and Treasury Secretary met with congressional leaders to discuss a ginormous bailout plan to save the banking system and, by extension, the economy itself. In this context it’s hard to fault a generation of readers who looked at what appeared to be an apocalyptic job market and wondered bleakly about their family’s future. No surprise, then, that that powerful metaphors for cut-throat competition and the extinction of upward mobility that Collins provided landed with such impact: child-sacrifice as a means of escape from, to use Sam Shepard’s phrase, “the starving class.” Indeed, the literally hunter-gatherer practices of protagonist Katniss Everdeen speaks to a world hit by permanent recession, its youth culture stripped of all its glitzy millennial tech. (Which is why I find this tongue-in-cheek piece about what apps she should use so hilariously depressing in its unintended irony.)

Still…

With all these concrete, real-world counterparts to the nightmare world of The Hunger Games, why does it seem that what might strike deepest at the teenage heart is its somewhat abstract indictment of today’s apparent mediation of… well, everything? Time and again, and more so as the plot progresses, the media are depicted as cutting us off from the deepest parts of human existence itself. This all-encompassing mediation serves purposes both political and entertainment-oriented… and actually, what’s so compelling about Collins’s ideological maneuvering on this point is how she conflates the two. On a societal level, The Hunger Games says, entertainment is always political.

So is it really the kids who are killing each other… or is it the mass media? Or, just maybe, is the influence of the media doing something far worse to them?

Consolation Prizes

Anyone familiar with the premise of The Hunger Games and the fact that its title refers to a widely broadcast competitive event—a bit like the World Cup, the Super Bowl, and the Oscars all rolled into one—is probably quick to realize that it represents the ultimate example of reality TV. In that sense it shares much in common with:

Anyone familiar with the premise of The Hunger Games and the fact that its title refers to a widely broadcast competitive event—a bit like the World Cup, the Super Bowl, and the Oscars all rolled into one—is probably quick to realize that it represents the ultimate example of reality TV. In that sense it shares much in common with:

- Stephen King’s The Long Walk (named one of ALA’s best all-time books for teens in 2000)

- Not one but two flicks from 1975—Rollerball and Death Race 2000

- Kinji Fukasaku’s based-on-a-novel cult movie Battle Royale (which just so happens to be out on DVD today in North America)

As any number of self-respecting geeks will tell you, Battle Royale most clearly resembles The Hunger Games because its competitors are high school students. Or is the correct word not “competitors” but “contestants”? The answer may lie in another well-known Stephen King tale, The Running Man, whose death-by-game show premise is played for dark humor while in her novel Collins, by contrast, rarely cracks a smile. After all, aren’t traditional game shows the forerunner of today’s competition-style reality series, the archetype of which is Survivor? Come to think of it, “Survivor” might be an apt, if rather bland, alternate title for The Hunger Games if ever there was one. But even that show is not the exemplar in terms of The Hunger Games’ critique of today’s let’s-crown-a-new-celebrity-from-out-of-nowhere brand of faux populism (or, from a media literacy perspective, feel free to replace “crown” with “manufacture” ). That, of course, would be American Idol.

But are the same teens who helped make American Idol a hit—and, more recently, all the clones following in its wake—the same ones who made The Hunger Games the object of the latest cross-media mega-fandom? Sure, but that’s not a contradiction. Like many works of “dark” pop culture, The Hunger Games is just as often masochistic as it is inspirational: it might attack the unsavory aspects of ourselves that we secretly suspect exist (after first projecting them outward for safety’s sake) but then it artfully persuades us that we’re so much more than those aspects. After all, as Katniss’s friend Gale remarks in one of the film’s better early scenes, “If we don’t watch, they don’t have a Game.” Implicit in this statement is the radical suggestion that, ultimately, there is no they: the Games are for the audience’s supposed edification, and if the audience tunes away from the same show that is literally killing them and their loved ones, for whom would it then be produced?

Or, because I could very well be wrong about the audience for all these current singing-and-dancing shows overlapping with HG fandom, why don’t you please just ask the teen fans you’re friendly with and tell me what they say?

While you’re at it, you may want to prompt them to share what they know, or sense, about non-scripted TV in general, especially those series that purport to feature “real” families/workers/adventurers/celebrities going about their everyday lives while the cameras roll. As a first step in checking their understanding of the constructed nature of all media messages, you might want to draw attention to the methods by which reality is augmented or filtered in these shows (omitting the boring parts, editing for dramatic conflict, selecting music, etc.). To encourage critical thinking on a deeper level, you might then ask in what ways the knowledge that they’re being filmed might change people’s behavior, consciously or unconsciously. And, hey, if this is a tricky idea to explore, just ask adolescents how their actions and speech might change if they were being broadcast to thousands, maybe millions, of viewers. (I happen to believe that all valuable criticism, including all critical literacy, stems in part from self-reflection—I’m funny that way.)

The essential question in this inquiry thus becomes to what extent the word “reality” in the term “reality TV” serves to mask the fact that this type of content is, in many important ways, the least real of any television programming.

When Life Becomes Fake

In any case, if the teens you know are stumped by these kinds of questions, all they need do is consult The Hunger Games. That’s because, courtesy of our narrator Katniss, readers are treated to a from-the-inside-out crash course in media literacy. Always conscious of where the cameras are positioned, and what’s being shown—or, often more crucially, what’s not shown—the novel’s first-person perspective effectively provides us with an ultra-candid sense of what it’s like to be a reality TV star in real time. And although her knowledge of how this so-called reality is constructed by media makers increases throughout the story, Katniss enters the process with substantial prior knowledge as an audience member herself. Moreover, this is knowledge that she has clearly thought about critically, even if this may seem like no more than repeating rumors. Here she is on a former competitor (or “tribute”) named Titus:

There are no rules in the arena, but cannibalism doesn’t play with the Capitol audience. So they tried to head it off. There was some speculation that the avalanche that finally took Titus out was specifically engineered to ensure the victor was not a lunatic.

Yet not only does Katniss become more aware of the behind-the-scenes manipulation of what are ostensibly real events, she privileges us with her insider take on which elements of reality do or do not get shared with the general public. This is most evident in the famous scene where she bedecks a fallen friend with flowers, an act of symbolic defiance that she hopes will make a subtle impression on viewers but later realizes has not made it into the official “cut” of the Games. Using the terminology of moving-image-media (e.g., “shots”) she increasingly comments on the kind of content that TPTB approve or disapprove, and at one point analyzes how/why specific footage has been vetted. In this way, The Hunger Games also functions as a nice intro-level text on censorship.

Significantly, Katniss also comes to notice the production choices that skew the representation of “reality” in a certain direction. This is how she describes her emotional recoil to a highlights-style video recap of events:

There’s this sort of upbeat soundtrack playing under it that makes it twice as awful because, of course, almost everyone on-screen is dead.

Pretty cool, huh? With this kind of observation we get the convergence of media literacy and moral/political questions. And this widening of the gap between Katniss and the target audience of the Games’ broadcast becomes more and more pronounced. While she begins the novel closer to the typical viewer—she never explicitly considers herself anything other than this—her own personal experience comes to render as rather grotesque the self-centered, morally myopic viewer who simply wants to be entertained, as shown in this water cooler moment:

They chatter so continuously that I barely have to reply, which is good, since I don’t feel very talkative. It’s funny , because even though they’re rattling on about the Games, it’s all about where they were or what they were doing or how they felt when a specific event occurred. “I was still in bed!” “I had just had my eyebrows dyed!” “I swear I nearly fainted!” Everything is about them, not the dying boys and girls in the arena.

In this sense, then, Collins is addressing the classic media lit question of “How might the same message make others feel?” Indeed, one might claim that this is truly the beginning of a political awakening for Katniss, one that is played out in the remainder of the trilogy (complete with additional themes related to media and society). Yet it all begins with the realization that one has been cut off not just from the real stories of other people, but alienated from one’s own store of basic empathy.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The reason this mechanism is so effective is that the public face of media is so good at pretending to care, as embodied by the character Caesar Flickerman, a Ryan Seacrest-type who engages in mindless banter with the tributes with the exception of the occasional probing question that is meant to lend a bit of depth to the proceedings. Moreover, Flickerman—his very name suggestive of moving-image media, as well as his/its lack of any real substance—is careful to cast himself not as a spokesperson for the Capitol, but rather as a viewer surrogate. This is especially evident when he does things like conjecture on what constitutes “the real excitement” for the audience, not just asking the kinds of questions that get at what viewers want to know, but explicitly framing them as such. As a result, he also subtly positions the audience as being like-minded to him, in a form of counter-projection… and in the process uses this identification to influence the audience according to the Capitol’s agenda. Want to introduce some critical literacy into your discussions of The Hunger Games? Just ask its young readers to think about how they feel when TV/radio hosts or sports commentators present themselves as fellow fans, and how this might encourage one to keep watching/listening.

According to some online sources that I’ve seen, the number one aspiration of teenage girls these days is to be a reality TV star. But even if the numbers are off, or decline, Katniss remains a powerful cultural role model in this respect. I say this not simply because, through her, young people can get a sense of “looking behind the curtain” of media production and become cynical about the entire process. Rather, by following how she navigates this landscape and by gaining insights as she gains them, fans can begin to notice the potential for more meaningful, personal, and authentic engagement with media messages and objectives. In this context, then, it might be heartening to recall that a recent poll indicates that reality TV might actually exert a positive influence on girls.

But how is Katniss to shift from a malleable doll at the hands of media makers to a fully empowered participant? It’s not an easy road for her, nor one that she really does more than merely set out upon in the trilogy’s first installment, but it’s certainly one that’s worth exploring further…

***

Okay, so more on The Hunger Games over the next few days, including a few more thoughts on the new film (which I was able to catch last night). [Update: here’s Part 2.]But I should point out that while Flickerman’s role as outlined above is made quite vivid in the film, unfortunately most of Katniss’s growth as a media literate teen has gone missing. Oh, and if you’re reading this and you don’t particularly care for the franchise, the new film, or all the hype around both, please feel free to chime in as well. It’s all part of the conversation. Fans—and anti-fans—are always welcome here.

Filed under: Fandom, Media Literacy, Movies, Social Studies, Television, YA Literature

About Peter Gutierrez

A former middle school teacher, Peter Gutierrez has spent the past 20 years developing curriculum as well as working in, and writing about, various branches of pop culture. You can sample way too many of his thoughts about media and media literacy via Twitter: @Peter_Gutierrez

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

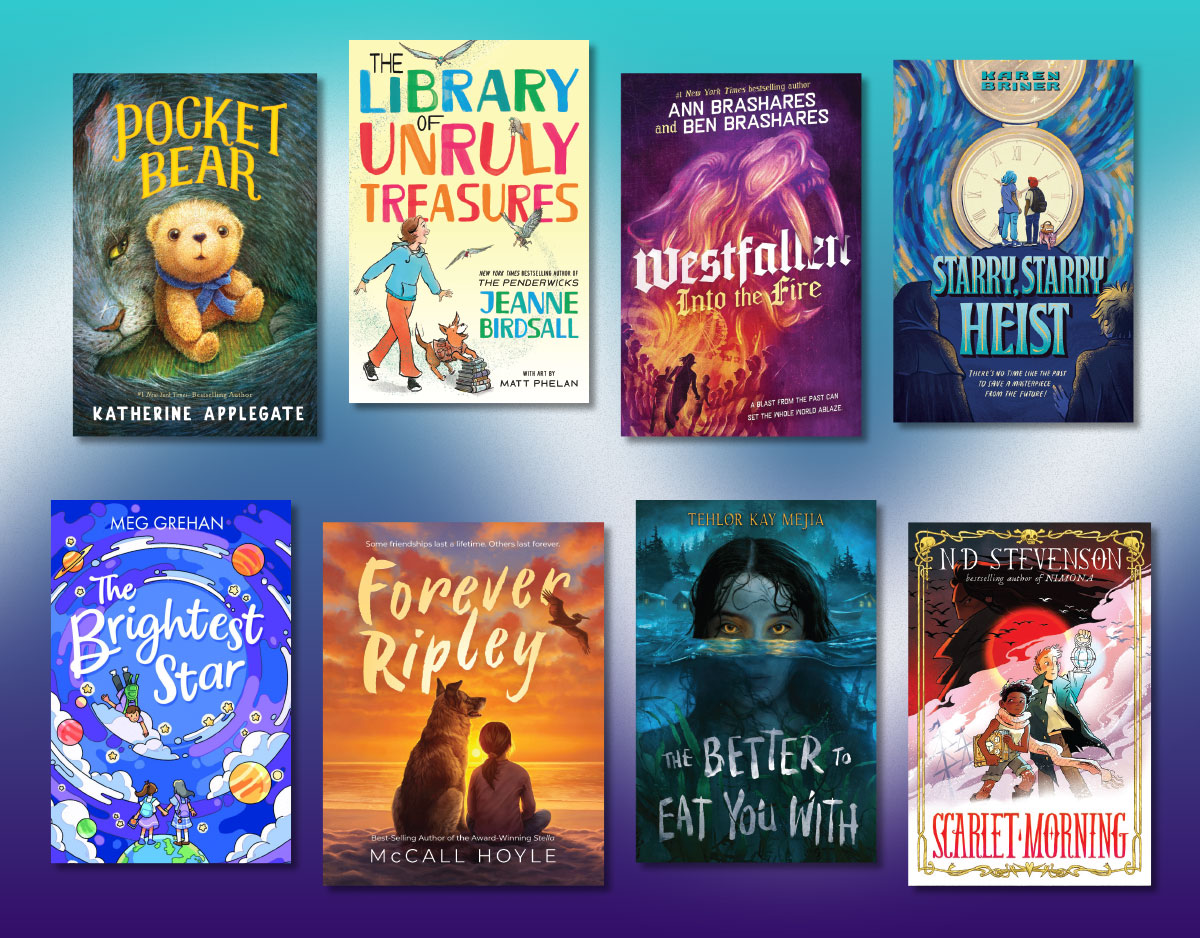

READ! What’s New in the READ Poster World in 2026?

Cover Reveal and Q&A: A Place to Dance by Eric Rosswood with Richard Lamberty, and illustrated by Vincent Chen

The Shiver of Christmas Town | This Week’s New Comics

The Right Back at You Project: Making Change, One Letter at a Time, a guest post by Carolyn Mackler

The Classroom Bookshelf is Moving

Our 2026 Preview Episode!

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT