SCROLL DOWN TO READ THE POST

Infotention and digital citizenship

Confessions:

I used to be smarter. I used to be a better friend. I used to be able to get more done.

I think the same may be true of my students.

Sherry Turkle, MIT professor and author of Alone Together: Why We Expect More From Technology and Less From Each Other, describes the research on multitasking–it degrades our performance.

In this video and several others, she advises that we need to value and teach uni-tasking.

I recently discovered that Huff Post now has a section on Uni-tasking.

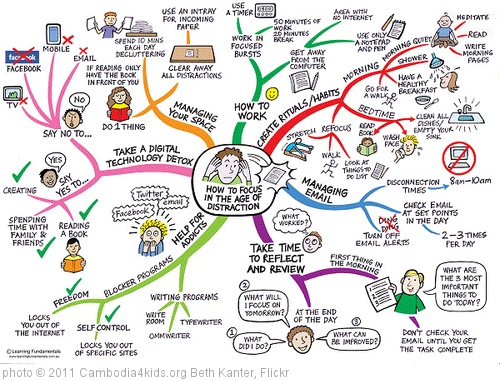

In his book Net Smart: How to Thrive Online, Howard Rheingold describes attention as the fundamental literacy and devotes a section to “Attention! Why and How to Control Your Mind’s Most Powerful Instrument” and this sub-chapter: “Conscious Distraction: Are You Captain or Captive of Your Attention Muscles?”

Rheingold writes:

It’s not that multitasking is always bad (except when it is – like when you are driving a car), or continuous partial attention (such as surfing the Web while talking on the phone) is always rude and inefficient. It’s that too few have learned and taught to others the skills we need to know if we are to master the use of our attention amid a myriad of choices designed to attract us. A significant part of the population has not yet learned to decide when it is appropriate to share multiple lines of attention and when single focal point is necessary (and I’m not just talking about etiquette her but rather efficacy in business and personal lives), no have many people studied how attention can be trained. (15)

In The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, Nicholas Carr argues the Internet is an interruption system. It seizes our attention only to scramble it. We cannot focus on tasks like reading.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

We want to be interrupted, because each interruption—email, tweet, instant message, RSS headline—brings us a valuable piece of information. To turn off these alerts is to risk feeling out of touch or even socially isolated. The stream of new information also plays to our natural tendency to overemphasize the immediate. We crave the new even when we know it’s trivial. And so we ask the Internet to keep interrupting us in ever more varied ways. We willingly accept the loss of concentration and focus, the fragmentation of our attention, and the thinning of our thoughts in return for the wealth of compelling, or at least diverting, information we receive. We rarely stop to think that it might actually make more sense just to tune it all out. (from The Web Shatters Focus, Wired, 24 May 2010)

FOMO, or the fear of missing out, drives many of us toward continual monitoring of social networks. The New York Times’ Jenna Wortham, describes FOMO as

the blend of anxiety, inadequacy and irritation that can flare up while skimming social media like Facebook, Twitter, Foursquare and Instagram. Billions of Twitter messages, status updates and photographs provide thrilling glimpses of the daily lives and activities of friends, “frenemies,” co-workers and peers.

An edtech blogger Andrew Churches recently blogged that BYOD is a digital citizenship issue.

As soon as a school starts allowing students to bring their own devices into school, they begin to surrender some of their control of the learning environment to the students. They do not have the ability to dictate and control what applications are or aren’t on the students machines. They can not control the media the student may have on the device as the computer is more than just a learning tool its also the young person social medium and often entertainment center.

Schools also lack the ability to search the machine, it is not the schools machine, rather it is the private property of another individual.

The boundaries between home/personal use in its varied forms – whether this is homework, social connections, entertainment, games or even inappropriate activities become blurred. What they do at home comes both unintentionally and intentionally to the school environment

Something is going on and we’re going to need to address it when we get back to school. I think Andrew is right.

A couple of weeks ago, at SocialEdCon (formerly EduBloggerCon), I facilitated a conversation using Rheingold’s term Infotention as a theme.

I shared my confessions and my observations of students. Others shared similar concerns.

We are having trouble getting kids to focus online.

Even when their classroom teachers don’t see it–the windows open on students’ screens–the windows behind the digital storytelling tools, the graphic organizers, the simulations, the databases, are drawing their focus from their projects and the learning conversation.

We discussed possible solutions to feed or text creep and student FOMO.

- Having conversations about what is acceptable behavior during a particular class, during a particular assignment, in a particular space.

- Creating really engaging activities.

- Consequences for inattention

- Blocking

We discussed that the problem isn’t new.

- Kids always looked out the window.

- Peeked at magazines or books in their desks.

- Daydreamed.

I didn’t use to worry too much about a student occasionally checking her Tumblr or Twitter stream while taking a short break from a long task. We use many of these feeds for real-time search. But I think that for some students, the work of learning has become secondary to the lure of social activity.

I hate to say it, but just sometimes, the drama surrounding–who is going out with whom, or who is wearing what to prom, or whose mom is totally unfair–is far more compelling to students than the most urgent global crisis or even the most engaging self-selected creative project.

What my colleagues and I observe is not occasional. It is a waste of the precious time we have to influence learners and learning.

So, I think we need to do some serious thinking about September.

When we discuss digital citizenship, it’s not just about safety and e-reputation and bullying.

It’s not just about that very bad student doing a seriously bad act.

It’s about civics and manners and and attention and community and trust. It’s about learning that the people around you want and deserve your presence.

It’s about growing young people who know when to listen closely and read carefully and think deeply and when to avoid distraction.

And it’s also about new classroom management strategies.

I think Andrew Churches is right on target.

What is required is a deep understanding and acceptance of what is appropriate and right. It is setting a moral code that guides and protects the students. It is a ethic that the students themselves must take up and follow.

This is not saying the students are left to fend for themselves…. Rather it is a process of development of the guidelines that is shared and mutually agreed to. Each aspect is simple, understandable and supported by clear reasoning & justification. It is also a process that is reinforced by all teachers as a consistent approach where the teachers model and enforce all the aspects. The process also requires there to be monitoring, intervention and consequences. Digital Citizenship is not limited to an agreement between the school and student it must also include the families

(Final confession: I know this is not my best work. I wrote it while I was building two presentations, writing a module of a grad course, and checking several feeds.)

Filed under: digital citizenship, information literacy, instruction, student work, students, unitasking

About Joyce Valenza

Joyce is an Assistant Professor of Teaching at Rutgers University School of Information and Communication, a technology writer, speaker, blogger and learner. Follow her on Twitter: @joycevalenza

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Books on Film: GUESS HOW MUCH for This Picture Book

Publisher Preview: Enchanted Lion (Spring 2025)

Mr. Muffins Defender of the Stars | This Week’s Comics

Heavy Medal Mock Newbery Reader’s Poll

Changing Stereotypes about Mental Health in Safe Harbor, a guest post by Padma Venkatraman

The Classroom Bookshelf is Moving

Our 2025 Preview Episode!

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT