SCROLL DOWN TO READ THE POST

Round 2, Match 4: This One Summer vs West of the Moon

|

JUDGE – ALAYA DAWN JOHNSON |

|

| This One Summer by Albert Martin Knopf/Random House |

West of the Moon by Margi Preus Harry Abrams |

One of the joys of first person narratives is being able to share, for a moment, the intimacy of another person’s perspective. It isn’t just the knowledge of their private lives or secrets that brings that richness–plenty of third-person narratives have those. It is that by filtering every aspect of the story through the narrator’s thoughts and feelings, we find ourselves, in a fundamental way, behind their eyes.

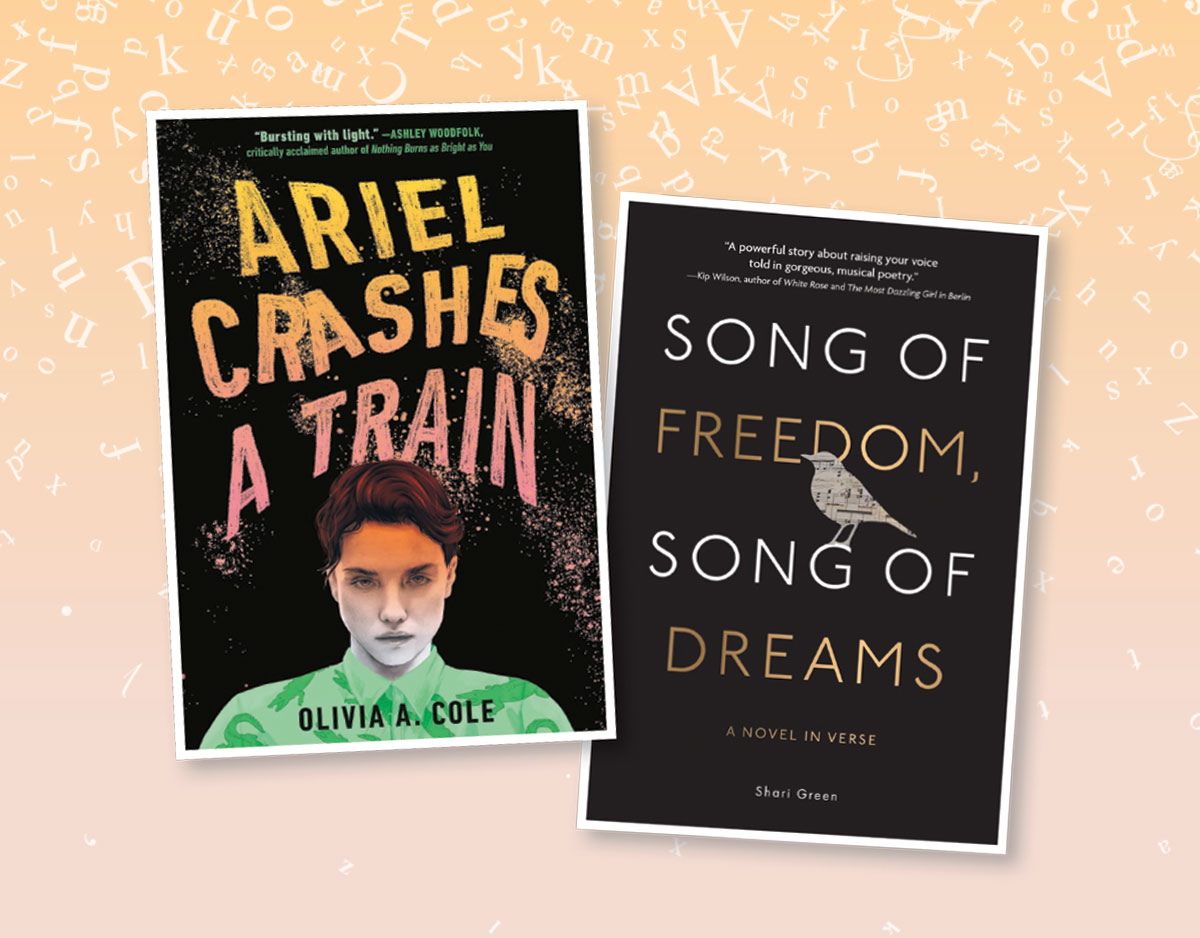

That intimacy is at the heart of the beauty of both of the works in my bracket, This One Summer by Jillian Tamaki and Mariko Tamaki and West of the Moon by Margi Preus. Graphic novel This One Summer handles this in a way that I found magnificently appealing, because it manages to perfectly encapsulate the first person feel in a medium that doesn’t always conform to my straight-laced novelist definitions of narrative mood. Jillian Tamaki’s evocatively detailed illustrations, which seem to pulse from the page with their combination of heavy lines and delicate shading, show us the details of fifteen-year-old Rose’s life one pivotal summer at her family’s traditional vacation spot in Awago Beach. This is an intimate story, deliberately circumscribed in scope, almost classically coming-of-age. Rose shares the summer with her friend Windy, a year and a half younger and like the little sibling that Rose has never had. But, as we come to learn in Mariko Tamaki’s organic and patient narrative structure, last year Rose’s mother was trying to have another child. Then she stopped trying, and the stress of whatever happened–a sharp-edged whatever from which all of the characters struggle to protect themselves, even when, like Rose, they don’t know exactly what it is–has stripped bare the dynamics of her once happy family. Rose blames her mother. In fact, she seems to find a perverse solace in a casual misogyny that her friend Windy finds progressively more uncomfortable. Her mother is irritable and withdrawn, and seems to resent everything about Rose’s ebullient, cheerfully brash father. Her father is at turns concerned and fed up, clearly wishing that his wife could forget the unforgettable.

Clearly, that is, to the reader–but not to Rose. As a matter of fact, Tamaki and Tamaki manage to drive their narrative in that narrow passageway between what their close first person narrator sees and feels, and what we as the readers are allowed to see and interpret differently. In one memorable sequence, Rose’s aunt and uncle come to the beach house for a few days, speaking cryptically in Rose’s hearing about how her mother is “holding up” and the time she needs to get over the whatever that’s tearing them apart. The tension goes from subtle and ignored to brutal and unavoidable in a masterful scene when Rose’s uncle playfully teases and eventually cruelly badgers Rose’s mother into entering the water with them. Rose’s mother refuses, politely but firmly. But the uncle persists, until his wife begs him to stop. At this point, Rose has had enough. But Rose doesn’t think this–she performs it, by diving into the water and swimming as far from shore as she can. Yet, despite her physical rejection of adult drama, she can’t help but turn around. And through her eyes, that metaphor made real though the power of graphic novel storytelling, we see the shapes of the argument, the movements of her parents and her aunt and uncle, the angry expressions, the shouting–and none of the dialogue. We are in Rose’s head, and Rose has refused to stay to hear.

One of the only times that the story breaks this narrative asceticism is towards the end, when we finally learn the whatever behind the family drama. And that conversation, to which Rose is not privy (and in fact, we’re never shown if in fact Rose does learn the real reason), struck me as the weakest moment in the narrative. Perhaps a story so fundamentally about not talking couldn’t believably resolve with a conversation. But to some extent I feel that that was precisely the intent–and it resolves with the wrong conversation. Not between Rose and Windy or Rose and her mother, but with her mother and a secondary character.

Margi Preus’s West of the Moon also makes ample use of the limitations of one narrator’s gaze–and, in this case, her imagination. A 19th century Scandinavian mashup of Bluebeard, Rumpelstiltskin and East of the Sun, West of the Moon (and probably a few others), West of the Moon resolves itself into a beautiful saga of sisterhood and storytelling and the profound sacrifices made by 19th century immigrants to America. It takes a fairy tale structure, but is deliberately agnostic on the fairytale mechanics–witches, warlocks, magic books, secret charms, and the cheating of a personified Death. Astri is a classic fairytale trickster–a persona more commonly male–who uses the tales of her Norwegian childhood to construct the narratives that she uses to survive in dismal and desperate situations. Her beloved sister Greta, for whose sake Astri fights the entire story, is hilariously more down to earth. Greta clearly loves Astri as fiercely as she is loved, but that doesn’t make her blind to her sister’s faults. Particularly–and hauntingly, as the story goes on–the loose relationship Astri has with the truth and honest behavior. In this instance, however, Greta’s suspicions turn endearingly comic:

“Was it really like that? About Papa and the seven-headed troll? Or were you maybe…stretching the story a bit?”

“Well, yes,” I say, considering. “I suppose it’s possible the troll had only three heads.”

Astri has a very peculiar view of the world. A view, we come to see, rooted in her youthful inability to understand the inexplicable, and at times tragic, behavior of the adults around her. She used the stories her parents told her to make sense of their behavior, and when harsh circumstances force her to approach her adulthood far too quickly (her greedy aunt and uncle sell her as a servant and potential wife to a wealthy neighbor), the stories become a defense and a survival mechanism. As long as Svaalberd, the hunchbacked “goatman” who has bought her to care for his goats and his filthy house, could be like the bear that took away the young girl in East of the Sun, West of the Moon, there is the chance that she can outsmart his curses and get away. If the “spinning girl” that she discovers locked in his storage shed can truly spin straw into gold, there is a chance that the two of them can trade her talents for enough goods to emigrate to America.

What particularly appealed to me about Preus’s novel was how it never wholly condemns nor rewards Astri’s ability to find and reshape the meaning of the world and her actions in it. I found it somewhat uncomfortable to read about her clever ruses to defraud people of money and other significant resources–people, it is clearly shown, who are not rich themselves. She abandons the Spinning Girl (an action she comes to bitterly regret) and robs and steals across Norway for a chance to get herself and her sister to America and their father. We are looking at the world so wholly through her eyes, so convinced of her own conviction about using fairy tale logic, that it is almost a shock when Greta expresses her disapproval of her sister’s behavior.

Neither This One Summer nor West of the Moon feature what I would call unreliable narrators. They are not trying to deceive the reader, nor are they fundamentally deluded or confused about how to interpret the world around them. What both of them rely on is the unreliability of every human perspective. But while This One Summer is a beautiful read, in the end my vote has to go to West of the Moon for sustaining its complex structure, and for the tantalizing hint that even while Astri is at her busiest spinning stories, she knows just as well as Greta that the truth hides behind them, slantwise.

— Ayala Dawn Johnson

This One Summer is the book that, out of all the BoB competitors, I will reread (the poetry, too, hopefully, and El Deafo with my little brother). For me, the complexities take a while to sink in. But did the story need to end with a conversation between Rose and Windy, or Rose and her mother? What will happen over that year, and the next summer? They’ll be some discussion, sometime, but Rose is pretty reserved about that, and that’s OK. Sometimes the carefully pruned storyline – made ever more evocative by Jill Tamaki’s stunning illustrations – doesn’t need to fully resolve. The summer exists in a kind of dream, and then they go back to the real world, where there may be a discussion (perhaps limited, knowing Rose’s family), but there will be honest love in the end, of some sort. I may not like Rose, but I feel sympathetic for her; on the other hand, in West of the Moon, I like Astrid. I agree with Johnson’s deep consideration of first-person narration and her final choice of Astrid’s story not because I like the main character, but because I can’t refuse a good “Viking” fairy tale.

– Kid Commentator RGN

When I read the verdict of this match, my first reaction was to stare blankly and numbly at the screen. And then I started, quite comically, hitting the computer keys and making unintelligible sounds of ire. What can I say? Teenage fangirls will defend whatever it is they love to the death. (Guilty as charged.) Now, my rant on the outcome is over. West of the Moon was the kind of book where every time you read it, you notice more details that you didn’t before. And because of that complexity, Johnson chose it as the winner of the battle. But, like most of the time this year (as I seem to, for the most part, hold the unpopular opinion) I disagree. The ‘simplicity’ of This One Summer was what made it so appealing and enjoyable to read. And I’m not saying that it was just a book that had an easy-to-follow and straightforward storyline, but its smooth and subtle twists and its wonderful characters made even the most basic things have complexity and depth. West of the Moon, however, has a much more intricate plot and contains some of the best life lessons I’ve seen in a book this year. But here’s the thing: This One Summer has some of those morals too, but they weren’t as prominent. I think that if I were a judge, my decision would come down to two thing. The first being the book with the best writing. The second being the book that I would most likely reread. And in this instance I would probably pick This One Summer. But I’m not the judge, and the decision had good reasons behind it.

– Kid Commentator NS

THE WINNER OF ROUND 2 MATCH 4:

WEST OF THE MOON

About Battle Commander

The Battle Commander is the nom de guerre for children’s literature enthusiasts Monica Edinger and Roxanne Hsu Feldman, fourth grade teacher and middle school librarian at the Dalton School in New York City and Jonathan Hunt, the County Schools Librarian at the San Diego County Office of Education. All three have served on the Newbery Committee as well as other book selection and award committees. They are also published authors of books, articles, and reviews in publications such as the New York Times, School Library Journal, and the Horn Book Magazine. You can find Monica at educating alice and on twitter as @medinger. Roxanne is at Fairrosa Cyber Library and on twitter as @fairrosa. Jonathan can be reached at hunt_yellow@yahoo.com.

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Exclusive: Vol. 2 of The Weirn Books Is Coming in October | News

Take Five: Middle Grade Anthologies and Short Story Collections

The Classroom Bookshelf is Moving

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT