SCROLL DOWN TO READ THE POST

Enough with the CRAAP: We’re just not doing it right

It’s not the web it used to be and our traditional approaches to teaching about it no longer make sense. In fact, we teach strategies that often fail our students.

A new study from the Stanford History Education Group (SHEG): Educating for Misunderstanding: How Approaches to Teaching Digital Literacy Make Students Susceptible to Scammers, Rogues, Bad Actors, and Hate Mongers, reveals some of the issues.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Researchers studied 263 college students at a large East Coast state university and presented them with two tasks.

The first asked students to evaluate the trustworthiness of a news story from a satirical website. Two-thirds of the students failed to recognize the article as satire. The few who left the article to investigate the Seattle Tribune’s website found the clear disclaimer:

The Seattle Tribune is a news and entertainment satire web publication. . . .All news articles contained within The Seattle Tribune are fictional and presumably satirical.

The second task asked students to evaluate the credibility of an article on the Minimumwage.com website. Though the cloaked site claims to sponsor nonpartisan research, a quick search of its parent organization, the Employment Policies Institute, reveals connections between the Institute and a professional restaurant industry lobbyist with clear interest in maintaining a lower minimum wage.

Relating to the cloaked site task, the study noted that 85% of the college students neglected to explore beyond the site to investigate its trustworthiness, relying solely on the information the site itself offered. While 45% of the college students did reject the site, they “based their judgment on irrelevant features, like the site’s top-level domain . . . Only seven students out of 138 connected minimumwage.com to the public relations firm of Berman and Company”

Educating for Misunderstanding reveals that at the university level:

Students struggled. They employed inefficient strategies that made them vulnerable to forces, whether satirical or malevolent, that threaten informed citizenship.

Overall, the study concluded that students:

- Focused exclusively on the website or prompt, rarely consulting the broader web.

- Trusted how a site presented itself on its About page

- Applied out-of-date and in some cases incorrect strategies (such as accepting or rejecting a site because of its top-level domain)

- Attributed undue weight to easily manipulated signals of credibility—such as an organization’s non-profit status, its links to authoritative sources, or “look” (p. 3)

So, what do we do?

Well before they reach the university, it’s time to put down the checklists and the score cards. And it’s beyond time to lose the artificial hoax sites. In many cases the students failed using approaches we’ve promoted.

Alarmingly, students’ approach was consistent with guidelines that can be found on many college and university websites. Sometimes these materials are just plain wrong. Sometimes they are incomplete. Sometimes they are so inconsistent that they offer scant guidance for navigating the treacherous terrain of today’s internet. Educational institutions must do a better job helping students become discerning consumers of digital information.

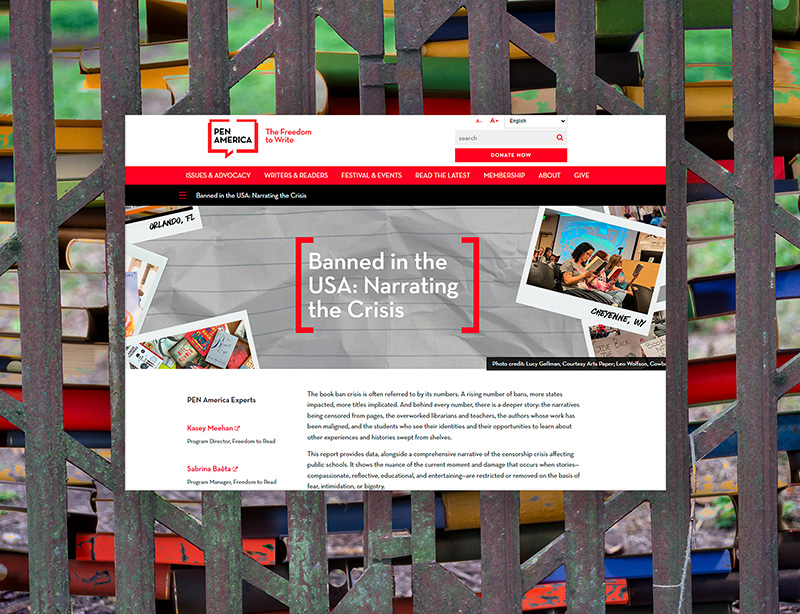

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Educating for Misunderstanding, as well as other recent work by SHEG and Mike Caulfield, reveal that traditional digital literacy tools–guidelines like the CRAAP test– simply do not work when faced with a web filled with hoaxes and deep fakes and cloaked sites and source hackers and scammers.

In fact, the old tools do more harm than good. Using top level domains, About pages, and update frequency as binary heuristics for authority are dangerous practices to promote. Believing in the inherent trustworthiness of .orgs; noting a site’s attractive design and lack of typos; and celebrating the inclusion of footnotes are ineffective strategies for fact checking.

Sometimes, you’ve got to leave the page. All the careful reading and spotting of clues won’t work when the answer is not on the page itself–when the page, or the image, is professional designed to deceive. You need to use tools like reverse image searching, triangulation and seeking original sources.

When confronted with dubious claims, Caulfield’s SIFT (The Four Moves) suggests students:

Check for previous work: Look around to see if someone else has already fact-checked the claim or provided a synthesis of research.

Go upstream to the source: Go “upstream” to the source of the claim. Most web content is not original. Get to the original source to understand the trustworthiness of the information.

Read laterally: Once you get to the source of a claim, read what other people say about the source (publication, author, etc.). The truth is in the network.

Circle back: If you get lost, hit dead ends, or find yourself going down an increasingly confusing rabbit hole, back up and start over knowing what you know now. You’re likely to take a more informed path with different search terms and better decisions.

In a landscape filled with information landmines, strategies like lateral reading are critical. Educating for Misunderstanding warns:

The basic assumptions of the CRAAP test are rooted in an analog age: Websites are like print texts. The best way to evaluate them is to read them carefully. But websites are not variations of print documents. The internet operates by wholly different rules.

Isn’t it time to ditch the checklists and offer our kiddos wholly different tools?

Resources and References

Civic Online Reasoning website

Stanford History Education Group website

Wineburg, Sam, Joel Breakstone, Nadav Ziv, and Mark Smith. (2020). “Educating for Misunderstanding: How Approaches to Teaching Digital Literacy Make Students Susceptible to Scammers, Rogues, Bad Actors, and Hate Mongers” (Working Paper A-21322, Stanford History Education Group, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, 2020). https://purl.stanford.edu/mf412bt5333.

Wineburg, Sam and Sarah McGrew. (2019). Lateral Reading and the Nature of Expertise: Reading Less and Learning More When Evaluating Digital Information. Teachers College Record, 121(11), n11. Preprint available.

Caulfield, Michael. (2019). Check, Please! Starter Course.

Caulfield, Michael. (2017). Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers

Filed under: technology

About Joyce Valenza

Joyce is an Assistant Professor of Teaching at Rutgers University School of Information and Communication, a technology writer, speaker, blogger and learner. Follow her on Twitter: @joycevalenza

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Review of the Day: Being Home by Traci Sorell, ill. Michaela Goade

Exclusive: Vol. 2 of The Weirn Books Is Coming in October | News

North Texas Teen Book Festival 2024 Recap

The Classroom Bookshelf is Moving

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT